This is a transcript of a presentation given 10th January 2017 as an assignment for the Human-Computer Interaction module of my MRes in Digital Civics at Newcastle University.

Hi and welcome to my talk. Today I’m going to talk about designing for human autonomy. I believe this is the biggest civic challenge facing HCI today.

First I should probably explain what I mean by that.

What I mean is that we should be free to use computers as tools to help us do whatever we want to achieve in our daily life. They’re supposed to make our lives easier, and right now they’re not.

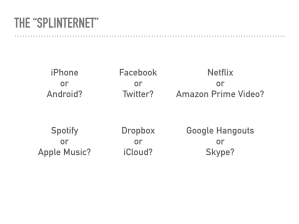

Instead of making things simpler, technology has made life more complex. We now have

chat services that can’t talk to each other

social networks that limit which friends we can interact with

devices that can limit what we can do with them

music we can’t share or copy

books we can’t swap or give away

And TV shows and movies we don’t own

The Internet promised us unrestricted, free-flowing information

But now it’s been divided and segregated, with barriers, signups and paywalls everywhere.

So what I want to do today is to look at how we got here, what it means for the field of HCI, and how we might be able to do something about it.

First, I’ll talk about two key trends that have shaped the current technology landscape – simplification and commercialisation.

Then I’ll look at how users can be better empowered by adapting their products and exploring their own data. change the status quo.

And finally I’ll look at the challenges involved – how to approach what is essentially a hidden problem for users, and how we might actually change the status quo.

OK, so how did we get here?

Well the first problem is that over the last couple of decades there’s been a relentless drive to simplify technology.

In some ways this has been a good thing – it’s brought computers to a mainstream audience – out of the workplace and into our pockets and our homes. But there’s been a downside too.

Since Apple launched the iPhone almost exactly a decade ago, they’ve marketed their technology as simple, magical, and wonderful. Their approach is to do things automatically for you so that you don’t need lots of features.

But as Cristiano Storni put it, magical design encourages people to be passive users who just do what they’re told.

We’re increasingly being told to just think of our hardware as black boxes; that we shouldn’t worry about what happens inside of our phones, cars, or laptops.

When you simplify like this, you dumb things down and disempower users.

Mark Weiser introduced the idea of seams to talk about this. The metaphor comes from tailoring – if you can access the seams of some clothing, you can unpick it and adapt it to your own needs.

In a technology context what this means is that having access to the “edges” of a product is important. If you think about a car radio for example – if your car has an aux socket, you’re free to plug in any music source you like.

But if it doesn’t, you probably can’t listen to music in the way you want to.

So when you look at what Apple’s done – killing off floppy drives, CD drives, and now even headphone jacks, you can see that they’ve actually made it much harder for people to adapt Apple products.

And it’s not just ports. With things like DRM and geo-blocking, companies are trying to control the experience you have with a product after you’ve bought it.

Technology is getting more and more opinionated and users are losing out.

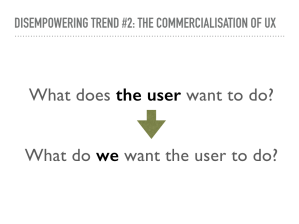

Which brings me nicely onto the second trend – the commercialisation of user experience.

If you think of a software product like Word, that you used to buy in a box and install, Microsoft didn’t care what you did with it. They’d sell more copies if they offered more features.

But now with the shift to cloud-based services, companies are changing the user experience to meet their own needs first, maybe disabling a feature to get you to upgrade or removing features so they have less code to maintain.

There’s been a massive shift in designers’ thinking from “What does the user want to do?” to “What do we want the user to do?”

This shift has happened because of the economics of the Internet.

People expect the Internet to be free, but companies have to make money somehow, so they get you to look at ads instead.

But a company like Facebook wants you to see their ads not anyone else’s, which is why they make it hard and undesirable to leave.

It’s not in their interests to let you easily move your data or interact with friends on other social networks.

And in order to get you to stay, companies like Apple and Google build up whole ecosystems of products so you can in theory get everything you need from that one company. All the big companies are at it.

But of course that’s nothing like the reality we live in. We use lots of different services, devices and providers.

So you end up with messy situations like this – I have 5 different representations of my family across the Internet – each with separate accounts, payment systems and preferences.

I think we deserve better.

So that’s the problem and how we got here.

What can we do about it, and what’s being done already?

Let’s start by looking at the three waves of HCI. Originally people were just operators of machines.

Then we began to recognise that computers are tools that people can use to help them with the tasks they need to do. And now technology’s entered all aspects of our lives so we have experiences with technology for leisure not just work. Design is focussing more and more on the individual, things are moving in the right direction.

We’re well into the second decade of the third wave, and things are still fairly chaotic, but one thing that’s become clear is that we need to allow for a secondary design process with products – where people adapt products in unanticipated ways.

This is called Design after Design, or Adaptive Design. There’s also the idea of seamful design. The Raspberry Pi is a great example of this – a product that is designed to be adapted.

This idea comes through in Forlizzi and Battarbee’s model of user-product interaction which was one of our set readings. They describe three types of interaction –

- cognitive when you spend time thinking about how to perform your task

- fluent, when you lose yourself in the task and forget about the product, and

- expressive interaction is when you form a relationship with the product by personalising it and customising it.

One area where empowerment is central to the design is Personal Informatics – using software and devices to track aspects of your life to give you insights.

Li et al came up with this model of the different stages a user goes through with a personal informatics system, and the last three are particularly relevant to what I’m talking about – you organise the data you’ve collected, reflect on it, explore it and learn something new that ends up with you being empowered to make changes in your life.

I think that when it’s done well, this is possibly the best example we have today of technology that really does empower users.

I think this growing focus on data is really central to empowering users, and I’m pleased to see that this has actually been recognised as a sub-field of HCI in its own right – Human-Data Interaction.

The idea is that we need to start to think about people having a relationship not just with their products, but with their data.

In this paper, Mortier et al defined the field and talked about it having three themes – legibility, which is kind of about awareness,

agency, which is very much like the autonomy idea I’ve been talking about,

and negotiability, which is about your ability to understand and act on your data.

I think this is a really useful model for thinking about designing for human autonomy.

OK so to finish off, I want to talk just a little bit about the unique challenges of designing for human autonomy.

One problem with disempowerment is we don’t always realise it’s happening. You don’t feel constrained until you get a new phone, or switch to a different provider or want to do something unusual.

Facebook killed off its RSS feeds, but that wouldn’t mean anything to you unless you decided you want to read your Facebook messages in a different way, at which point you realise you can’t.

People just generally carry on with what they know. So what this means is that users aren’t always aware that there’s even a problem.

Which gives us a problem as researchers – it means we have to stop and ask that Digital Civics question we know so well, “who knows best”? If this isn’t something that users are shouting about, can we be certain we are right about it? Do we have the right to advocate for users’ autonomy?

It causes a problem in research too because you won’t necessarily be able to uncover these issues through a user workshop. You might have put your own design priorities first, which as we’ve learnt is generally a bad practice. So that’s one dilemma.

The other big dilemma is even if we can conceive of ways to empower users more with technology, how can we put them into practice when the tech world is mostly shaped by the private sector?

HCI researchers in academia can come up with great ideas but will struggle to get them adopted, while HCI designers working in industry will have no choice but to sacrifice user empowerment for the sake of putting commercial motives first.

I actually think that this problem area is something that we’re best placed to research from academia, because companies won’t spend money on researching ideas that might harm their profits – and that’s actually the main reason why I moved back into academia.

There’s no doubt, it’s going to be really hard. But it wouldn’t be a challenge if it wasn’t.

I’ve got lots of ideas on how we might start to tackle this, such as using agonistic technology to get people talking and raise awareness, or presenting new data back to people in the same way personal informatics systems do, or looking for solutions that can benefit businesses too, such as personal data lockers.

But for now I’ll finish my talk with a summary…

Current commercial trends have taken power away from users.

When companies remove ports or close APIs, they limit our agency.

You can empower users by giving them meaningful access to their data so that they can draw insights and make changes.

This is a particularly hard problem to solve, because it involves going against the current market trends, and because many users aren’t even aware of the problem.

But we can make a difference, if we start the conversation, explore the problem and start prototyping solutions that offer new insights.

Thank you for listening (reading).

This is a transcript of a presentation given 10th January 2017 as an assignment for the Human-Computer Interaction module of my MRes in Digital Civics at Newcastle University. It can be downloaded in PDF form (with speaker notes) here.